So, I have a confession to make. I’ve been watching the development of generative AI over the course of the last few months with interest, but haven’t really experimented with it much until quite recently. And that includes… the blog post I published last week. I used ChatGPT to produce it because I was keen to (a) see what it was capable of and (b) see whether something co-produced could generate genuine and thoughtful discussion. (I’ll get to my definition for “co-produce” in a minute.) I now have answers to both those questions, but first, let me tell you the story of how the post came about.

(Oh, by the way – this blog post was not written with the help of any AI. Sorry to interject, but I knew some of you would be wondering. Back to the story.)

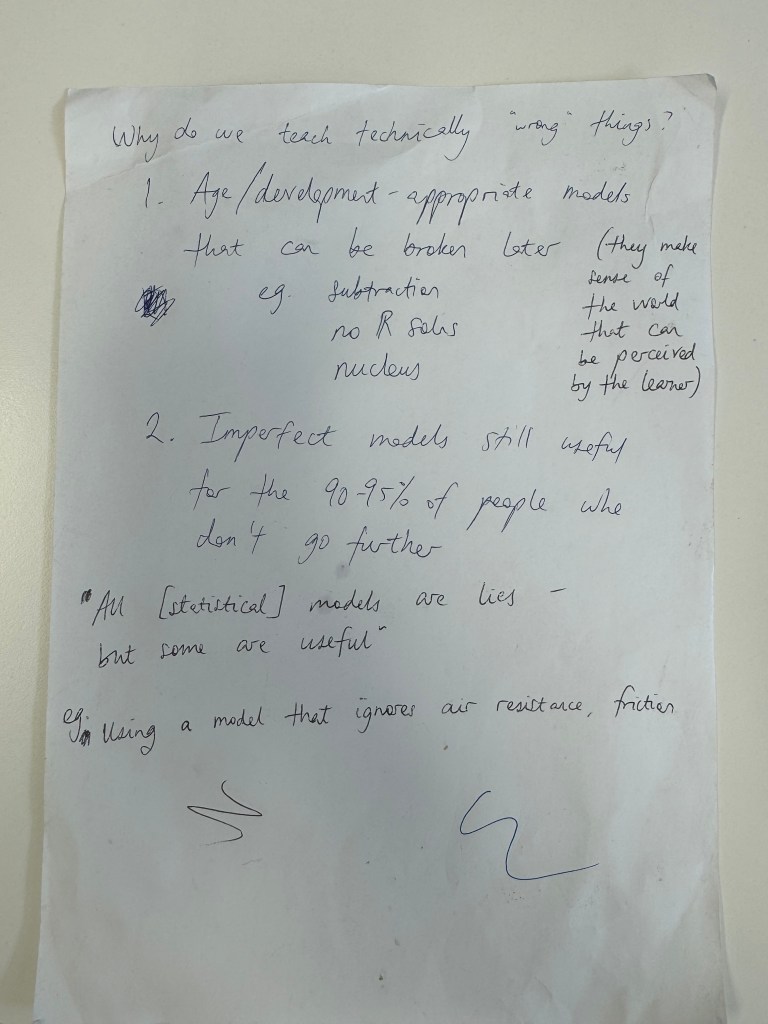

Earlier this year I was in a conversation with some preservice teachers. One of them asked me a question and I gave him an answer on the spot, but as I reflected on that conversation later that day, I realised that I had never really articulated a full answer to this particular question up until this day. So I hastily jotted down the outline of the answer I gave, so that I wouldn’t forget the key points, and thought to myself that I might revisit these notes and turn them into something a bit more systematic. Here is that page of notes. Yes, I know it’s messy (I told you it was hasty!):

Some time later I read about how OpenAI had updated ChatGPT with some visual recognition models. I wondered, “Could ChatGPT read this and make sense of it? Could it do more than make sense of it – could it expand on the thoughts that I’d written down?” If you read the blog post linked above and make a comparison, you’ll see it did a pretty decent job (and even accurately identified the source of the quote, which I couldn’t remember when I jotted this down).

There’s still much to explore and question, but this small experiment has definitely given me some early answers to the questions I posed before. What is ChatGPT capable of? A coherently written post that successfully expands on my basic ideas, at the very least. That said, I did find its writing style to be quite stilted. In particular, the sentence construction and cadence were remarkably consistent all the way through. It reminded me of this:

ChatGPT defaults to write more like the first paragraph than the second and third. This plain style is a known phenomenon, and many have written about it. I acknowledge that it can be coached to write in different ways but I did want to see where it naturally landed – and since I imagine that I will use ChatGPT in the future to save myself time, I wanted to see what it was capable of doing without copious amounts of effort from me. I actually enjoy the process of writing and editing, so if I was going to invest significant time into writing something (like this post), then I would rather spend that doing the writing myself rather than wrestling with the LLM to get it to do the work for me. But this is noteworthy nonetheless. And this is where I come to my definition for “co-produce”, which is a phrase I’m adopting because I don’t feel comfortable saying that I wrote the original blog post. (And based on my knowledge of how large language models work, I don’t even know if I would call what ChatGPT does “writing” either!) However, I didn’t ask the AI to brainstorm for me; I provided it a very concrete direction and asked it to expand on what I presented to it. If you’ll permit me to anthropomorphise briefly, we were partners in the process – hence “co-produce”.

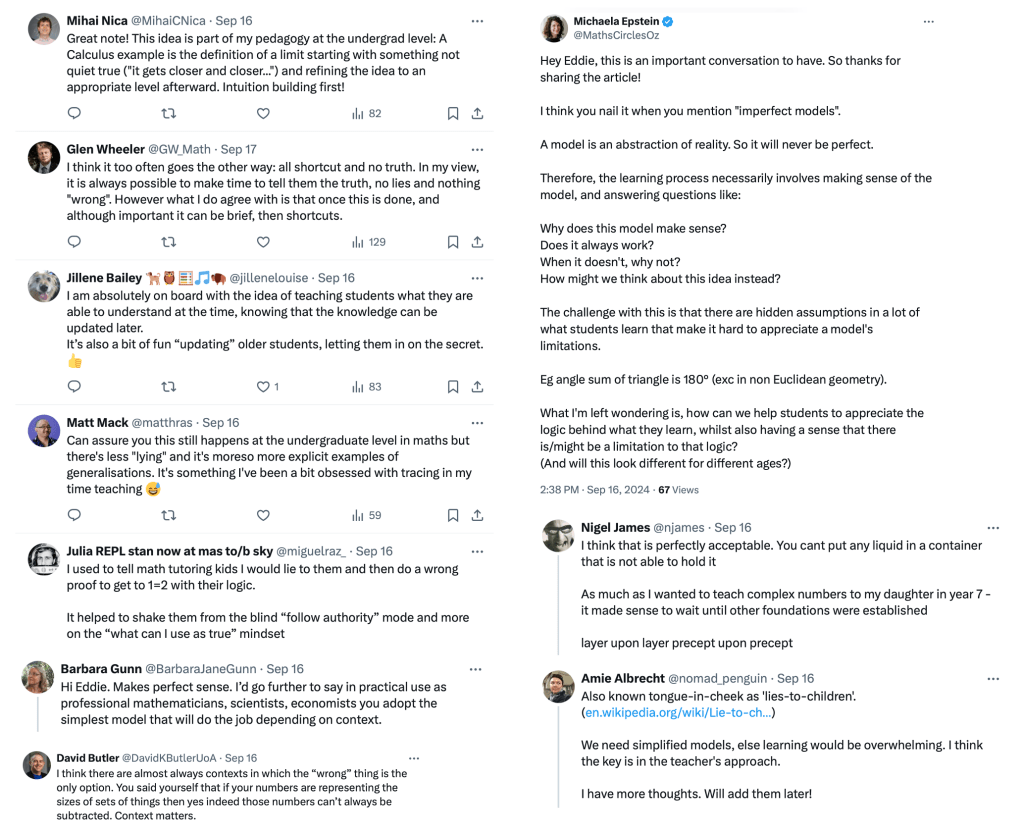

My other question was around what kind of discussion this would prompt. Answer: plenty. I’m posting these particular comments because they were posted publicly; I received even more responses in other private contexts where I shared the same post.

I do wonder if there would have been as much discussion if people had known from the outset that I’d used AI to put this together. Maybe if you were one of the people who responded in the first place, and you’re also reading this reflection of mine, you can throw your thoughts into the ring one more time for me.

Now, just so you know that I don’t think AI is going to replace us any time soon, let me share with you the next chapter of the story. I was at a PL session recently where we were presented with a very classic word problem, the kind that I would instinctively solve by introducing some algebra. But I wanted to try and see if I could explain it to the 9-year-old boy sitting next to me without appealing to algebraic techniques, so I drew this:

I asked ChatGPT, “Can you create accurate diagrams based on an image of hand-drawn text and diagrams?” And with its characteristic confidence, it replied: “Yes, I can help create accurate digital diagrams based on an image of hand-drawn text and diagrams. If you upload the image, I can analyze it and either recreate or enhance the diagrams digitally for clarity and precision. Let me know if you’d like to proceed with that!”

I did want to proceed with that. And here is what ChatGPT handed me:

OpenAI still has a ways to go yet! But it seems clear to me that we are still at the very beginning of learning how AI will change what education looks like.